The Vulture rises imposingly, isolated as it is between the plains.

The ancient mountain, dear to the Latin poet Horace, is a volcano. From the time of its formation, some 750,000 years ago, it has been the undisputed leader in geographical, botanical, zoological and anthropological events in the surrounding natural environment.

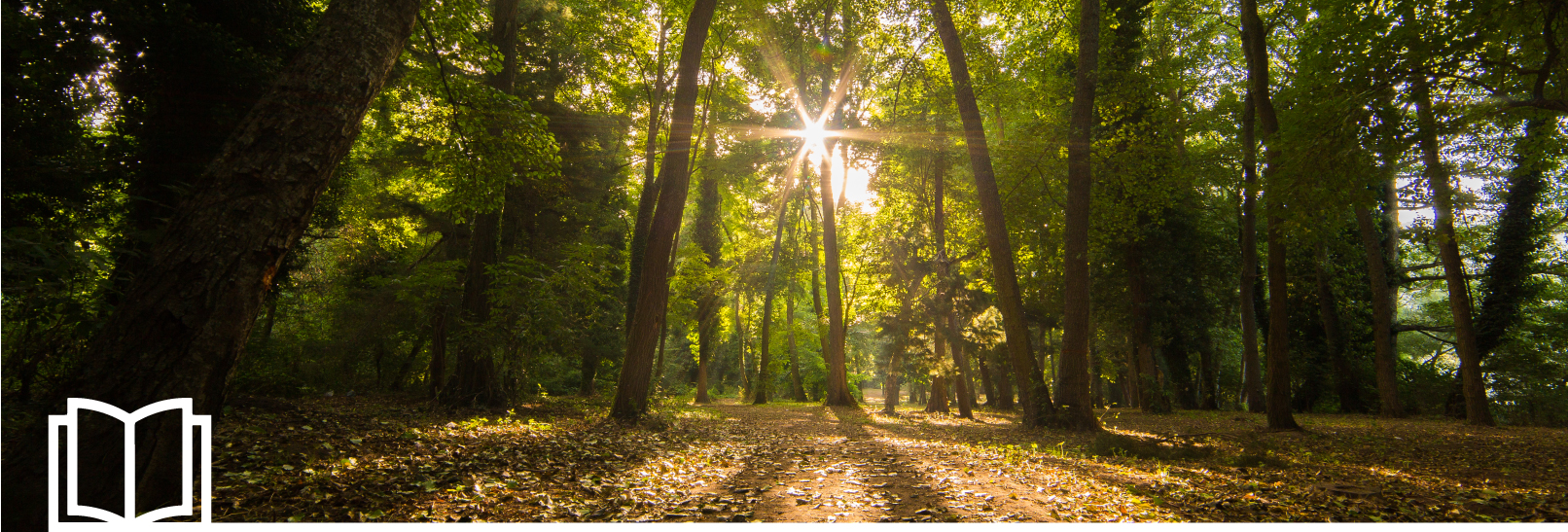

Since its last eruption, 125,000 years ago, the living landscape has been slowly but steadily developing, through glaciations and a fascinating natural and human history. One exceptional witness is a butterfly, a Miocene relict, a living fossil: the European Bramea, which still exists after millions of years in its ancient habitat in a small wood in Vulture.

The entire massif is included in the National Inventory of Geosites. Its collapsed caldera, completely reforested, with the two Monticchio lakes below, makes up the Zona Speciale di Conservazione (ZSC) Monte Vulture (Monte Vulture Special Area of Conservation).